Sagene

Oslo, Norway

Water cascades through the open dam gates by old industrial buildings along Akerselva in the Sagene district. Cultural heritage and historic architecture are tactically incorporated into urban regeneration. Myrens Verksted is one of several industrial heritage sites anchoring urban transformation. Today, the area is a business park adjacent to a 40-acre park with a large bowl-shaped grassy field creating a natural amphitheatre that is used in the summer by sun-seekers and for concerts and in the winter as a sledding area prized for sloping terrain from Maridalsvein towards the river.

Sagene

Sagene district is in the inner city, northeast of the city centre, on both sides of Akerselva.

The appellation "Sagene" finds its etymological roots in the industrial history of the district's locale alongside Akerselva. Derived from the plural form of the Norwegian word for "saw," the name pays homage to the abundance of sawmills and industrial activities that once lined the banks of the river. The integration of the past industrial architecture distinguishes many modern-day district urban developments.

Today, Sagene vividly embodies these post-industrial transformations; repurposed industrial buildings house businesses supporting the creative and knowledge economies instead of manual labour. For example, workers' housing near the industrial corridor is converted to park-facing townhouses near the vibrant river corridor. Small wooden houses built for labourers before the area was incorporated into Oslo are now homes to IT professionals, graphic designers, educators, and their families. Recent housing development includes construction on former industrial areas such as Lilleborg and Ringnes. This shift also reflects the urban policies implemented after the decline of traditional manufacturing, paving the way for a service-oriented economy and embracing what urban studies theorist Richard Florida coined the "creative class."

Sagene is the smallest district by area and has the highest population density and the largest share of the total area regulated as open space among Oslo's districts (20 per cent of the district area). Consequently, these unique factors contribute to the area's distinctive character, fostering a dynamic environment where people can live, work, and play.

Oslo’s red telephone booths

When one is not enough: Two iconic, historic phone booths in Sagene across from Sagene church and adjacent to Gråbeinsletta Park.

In May of 2022, the last public payphone in New York City was removed. Once an essential resource, tens of thousands of pay phones dotted the city; now, the last one was hoisted onto a flatbed truck and driven away. Gawkers bore witness to the end of a once routine aspect of city life. Ironically, this death knell was captured by these onlookers using their smartphones, snapping pictures over the shoulders of one another, and brandishing the profligate omnipresence of mobile phones in our daily lives. Bloomberg CityLab reported the event as the moment when "a line to New York City's past was officially disconnected." [1]

In contrast, many of Oslo's historic phone booths have found a different fate. Today, you can still find the iconic red “telefonkiosk” throughout the city. However, that doesn't mean you can make a phone call, as the dial tone went silent from the last operating phone in Oslo in 2016. This phone was in a booth in front of Majorstuhuset, a 1920s building fronting the metro station. I overlooked this last operating phone booth from my fourth-floor balcony for many years. Today, it is still there, as many of these structures remain, preserved as cultural monuments and persisting as repurposed community assets.[2]

Cultural Icons

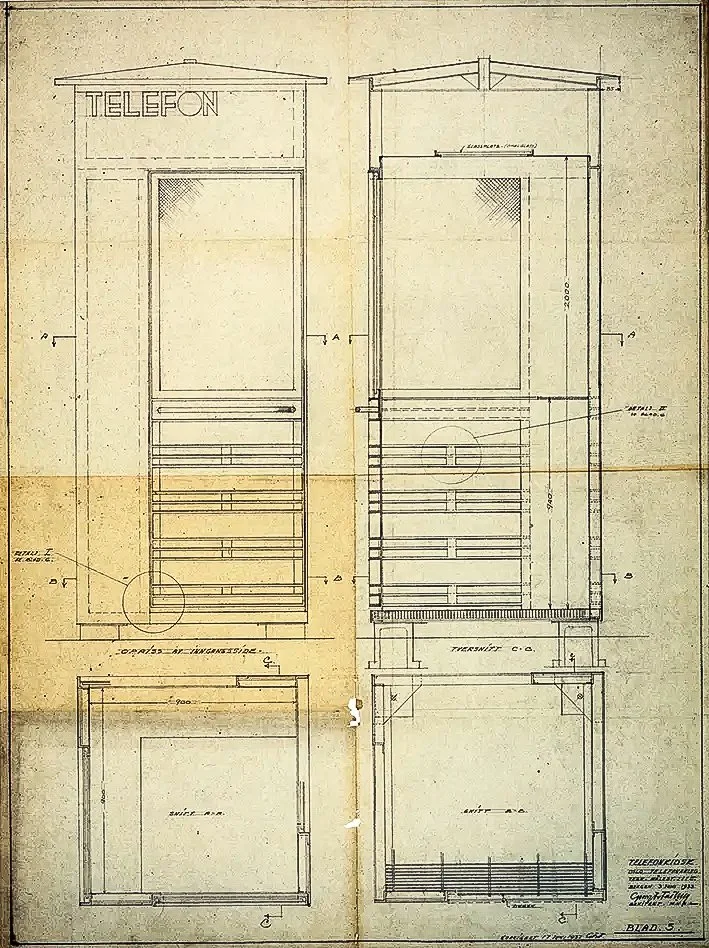

Throughout Oslo, the little red telephone kiosks punctuate the streetscape as bright and bold exclamation marks. They are a hallmark of the city, akin to London's red telephone boxes and beloved emblems of early 20th-century modernist design in Norway.[3] The booth was designed by Georg Fredrik Fasting in 1932, who won the competition for a public phone booth. His proposal exemplified the principles of functionalism, emphasizing simplicity, functionality, and the use of modern materials. Constructed from galvanized iron and riveted plates, the design featured a modern geometric sans-serif typeface. The first of these booths was installed along Oslo’s waterfront at Akershuskaia in 1933, marking the beginning of their citywide proliferation.

Architect Georg Fredrik Fasting’s drawing for the telephone kiosk, June 1933.

For many, the phone booths were the only option for making calls. Home telephones were rare in Norway at the time, making these public booths essential and critical for emergency communication points for the police, fire departments, and medical services. They were factored as part of residential planning and installed in coordination with housing developments to ensure residents had access to telephones.

They were vital communication points and, moreover, became meeting places where people congregated. Waiting in a queue around the kiosk became a distinct and recurrent urban experience. Neighbours would connect, share news, and gossip. Sociologist Eric Klinenberg developed the concept of "social infrastructure" in his book, Palaces for the People, which looks at the kind of public spaces that contribute to the public life of cities.[4] The kiosks represent the type of often overlooked spaces that maintain social connection, nurture public life, and enrich the social life of cities Klinenberg studied. In this way, they became a dimension of public space and public life of the city, providing a social infrastructure in excess of the telephone network.

From a neighbourhood point to meet up or hang out, the booths often were the canvas for local graffiti or a bold and decipherable declaration etched into the red panels of a heart and initials and even provided anonymity for making prank calls. For reasons such as these, the red phone booths, known as "Riks," hold a special place in the memory of Oslo residents. Accordingly, they have been memorialized in a book and exhibition and further venerated by Facebook pages for ‘friends of the telephone kiosk’ and a page that celebrates their history and curates their ongoing use.[5] Residents' stories recount, for example, leaving the house with enough change in their pocket and a name or number scribbled on the palm of their hand – perhaps to call a secret friend. They would arrive at the ever-present queue, dangling their legs from an adjacent bench and exchanging stories about local ongoings. Nils Marstein, an architect and the national antiquarian from 1995 – 2009, noted that many probably had their first kiss in the dim light around one of these telephone booths.[6] To this point, the book, Norges lille røde - historien om telefonkiosken [Norway's little red - the story of the phone booth] recognizes the booths as a ‘gathering point in the local community’ important for well-being and belonging.

The Decline of Public Payphones and New Connections

The practical necessity of public payphones has declined in Oslo since the 1980s. In 1967, only 44% of Norwegian households had a telephone, 74% by 1981. As private telephones became more common, the need for public phone booths diminished, and soon thereafter, mobile phones made them largely obsolete.

The extant red phone booths remain throughout the city. A Neighbor reads the titles on the kiosk shelf in the kiosk at Jacob Alls gate 58, in St. Hanshaugen bydel.

But the kiosk is not obsolete. Many of these iconic booths continue as meeting points in the neighbourhoods and are also repurposed as mini-libraries where people can "give a book—take a book." Vibeke Røgler, project manager for the reading kiosks, emphasizes the social function these booths continue to fulfil, connecting people through the exchange of books.[7] Røgler observes what Klinenberg has researched, that physical urban spaces can nurture public life.

Oslo's red phone booths are more than relics of the past. While their original function has faded, they continue to connect the community and persist as meeting points and cultural landmarks. These kiosks remind us of the evolving nature of urban spaces and the importance of preserving historical elements in modern cityscapes.

They are emblems of the city's architectural heritage and are enduring public spaces integral to city life [imagine a big red Riks’-sized exclamation mark here].

In the winter, the neighbourhood meeting place is used as for Christmas tree. From the sidewalk, to a short walk to the residence homes and many walk-up apartment buildings.

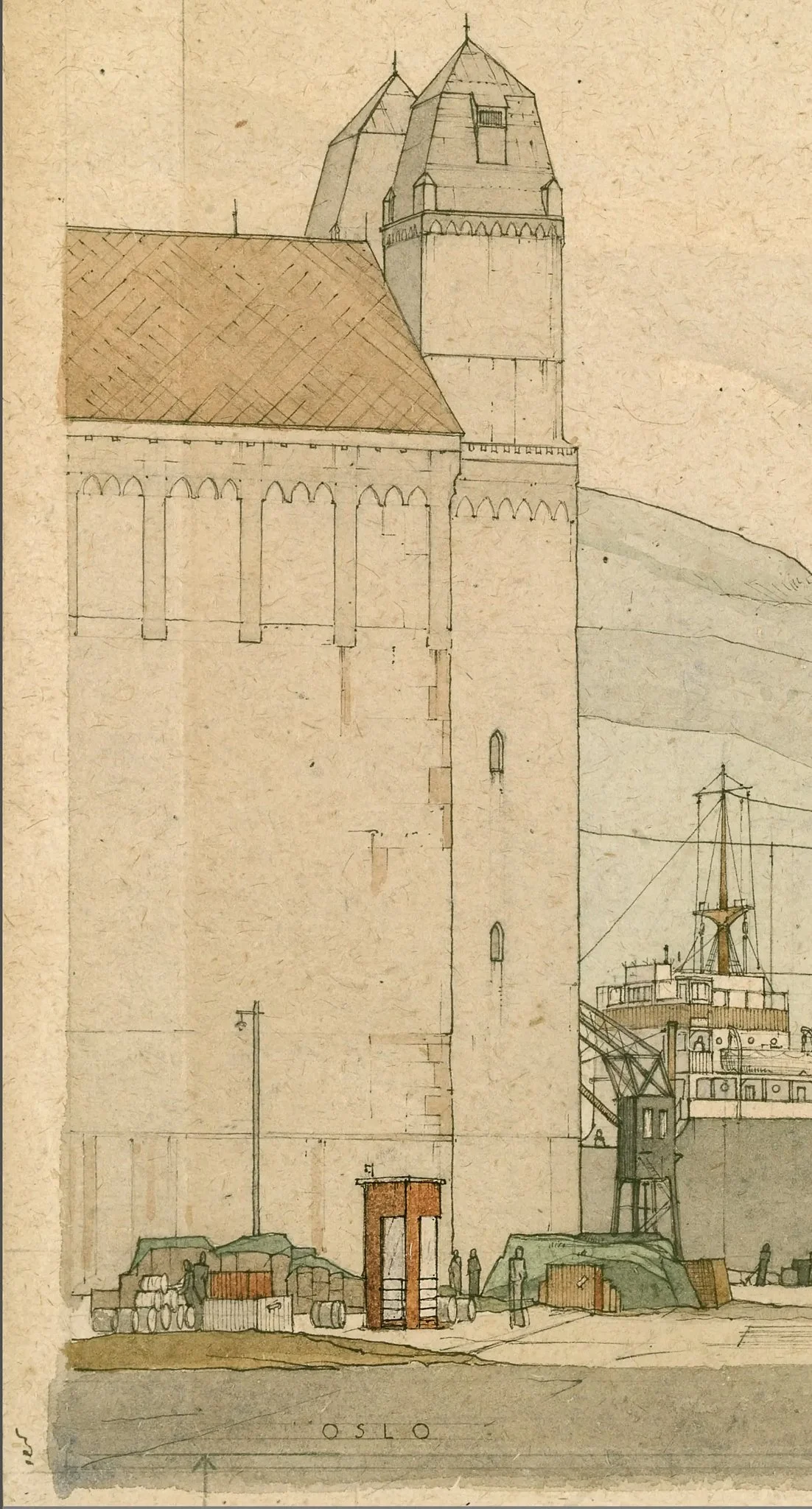

The red kiosk is pictured in a 1935 illustration by Frank E. Dodman—detail from a larger watercolour of the harbour and working life along the docks and adjacent silos. Oslo Musuem, byhistorisk samling.

[1] "NYC Says Its Final Goodbye to the Pay Phone," CityLab Culture, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com

[2] Recognizing their historical and cultural significance, the Norwegian government protected these kiosks as cultural monuments in 2007. There are now over 100 preserved phone booths across the country. David Brand, Madelaine Brand, and telemuseum Norsk, Norges lille røde : historien om telefonkiosken (Oslo: Norsk telemuseum, 2007).

[3] DOCOMOMO (Documentation and Conservation of buildings, sites, and neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement) recognizes these kiosks as important cultural and architectural icons.

[4] Eric Klinenberg and Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the people : how social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life (New York: Broadway Books, 2018).

[5] Facebook page: “Den Røde Telefonkiosken”, facebook.com/telefonkiosken/ and “Telefonkioskens venner”.

[6] Brand and Brand, Norges lille røde : historien om telefonkiosken, 15.

[7] The initiative to repurpose the booths as reading kiosks is supported by the Sparebankstiftelsen DNB and Telenor.